|

|

|

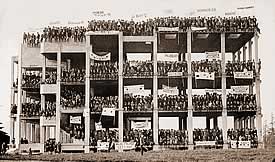

To help celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the passing of the University Act, we published this year TUUM EST: A History of the University of British Columbia, by Harry T. Logan, and in the brief history that follows I have borrowed freely from Professor Logan. I hope that what I have borrowed gives you some idea of the full story he tells so well. We could not have found a man more suited to write our history. One of the “founding fathers” of 1912, he has since served UBC as a member of the teaching staff and Head of the Department of Classics, as a member of the Senate, and as a member of the Board of Governors. In some ways our history is a record of perpetual frustration; we have never had enough staff, buildings, money, facilities of any kind. Our building programmes were halted by two world wars and by economic depression. We had to appeal to the public to persuade the government to move us from Fairview to Point Grey. Recently we have had to appeal for funds to pay for the buildings we need so urgently. But there is another way of looking at our history. The public has always responded. We have always needed more staff and more buildings because we have always had the one surplus that is desirable – a greater demand for education than our facilities could cope with. Since we are proud of what we offer and since we think it good for the community to have as many of our graduates as possible, we must sometimes rejoice that we have always had almost an embarrassment of students. In our jubilee year, let us remember that happy side of our history. And whatever our difficulties have been (and no doubt will be), let us look at what we offer, look at our present campus, remember our past, and enjoy some satisfaction at what has been achieved in fifty years. The history of the University during these fifty years runs parallel, in many respects, to that of the Province. As a state institution it depends mainly upon the public treasury for financial support. It has prospered with the prosperity of the Province. It has also felt the pinch of hard times; even to the point of threatened extinction. But throughout its half century of life, whether in adversity or prosperity, it has always had the devoted support of leading citizens, many of whom have served on its governing bodies. True to its Motto, TUUM EST, “It is Yours”, the University has served the interests of all the people of the Province. Within its walls the sons and daughters of our citizens have been given the opportunity to satisfy their needs for higher education and training. Slowly, year by year, decade by decade, the University has added to its facilities in response to the demands of its students and to the needs of the community it serves, until today its curriculum embraces most subjects of study offered in the larger universities of this continent. In its first Session, in 1915, the University, with a total registration of 435, was equipped to give courses in all years of the Faculty of Arts, for the degree of B.A., and courses in three years of Applied Science toward the degree of B.A.Sc. In 1958, with just under 10,000 students, full undergraduate degree work is offered for a total of 15 degrees distributed among nine Faculties. In addition the Faculty of Graduate Studies directs Master’s work for seven degrees, given in six of the nine Faculties, and Ph.D. work in twenty – four separate fields of study. The teaching staff in 1915-16, in all grades of appointment, numbered twenty-four; in 1957-58 the number exceeds 900, including demonstrators, assistants, lecturers and honorary lecturers, fieldwork supervisors in Social Work, and clinical professors and instructors in the Faculty of Medicine. In numbers of students the University of British Columbia stands second among the English language universities of Canada. It has graduated 26,000 men and women. A provincial University was first called into being by the British Columbia University Act of 1890, amended in 1891. Under this Act a Senate of twenty-one members was constituted and a McGill medical graduate, Dr. Israel W. Powell of Victoria, was appointed Chancellor. Regional jealousy between the Island and the Mainland killed this Act after several ineffectual attempts had been made to put it into operation. The Universities of Toronto and McGill then took the lead in promoting higher education in the Province. The Columbian Methodist College in affiliation with Toronto was formed in New Westminster in 1892 to give work in Arts and Theology. The College was soon entrusted by Toronto with all four years’ work, though the records show that very few students ever availed themselves of these facilities. Soon after work began in Columbian College, McGill University appeared on the educational scene, in affiliation with high schools, first in Vancouver, in 1899, and then in Victoria. A further stage of development was reached in February, 1906, when two Bills, drawn up in Montreal by McGill’s solicitors, were introduced in the Legislature in Victoria and passed, setting up McGill University College of British Columbia as a private institution under an independent governing body, known as the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, and giving courses “leading to degrees of McGill University”. McGill College carried on its work for nine years, giving up to three years in Arts and two years in Applied Science in Vancouver and two years in Arts in Victoria. In the last Session of 1914-15, there were 290 students in Vancouver, and 70 in Victoria. In the meantime the movement for a Provincial University had come to life again, quickened by inter-University rivalry and the widely-held conviction that the legislature had given McGill a position of advantage in recruitment of students from British Columbia in the senior years and in the professional facilities. All University graduates now united with professional organizations and the governing bodies of the Presbyterian, Methodist and Baptist churches in appeals to the Government to revive the earlier legislation for a provincial institution The government of Sir Richard McBride yielded and, under the leadership of the Minister of Education, Dr. Henry Esson Young, a graduate of Queen’s University in Arts and of McGill University in Medicine, two Bills were piloted through the Legislature: the University Endowment Act in 1907, and The University Act in 1908. These two pieces of legislation were the foundation on which was built the University of British Columbia. The government moved slowly in implementing these Bills. It was seven years after the University Act was passed before the University was ready to begin work. In 1910 a Commission of distinguished Canadian educationists chose the Point Grey site, thus relieving the Government of making a decision on the highly controversial issue which had wrecked the first University Act. Convocation met in 1912, under the Chairmanship of the first Chancellor the Hon. Francis Carter-Cotton. The University architects sketched plans for the new buildings in 1912. The Government appointed Dr. Frank Fairchild Wesbrook as President in 1913. The Board of Governors called for tenders for the buildings in June, 1914; on the outbreak of war in August, the tenders received were returned unopened. So it was that the University was compelled to begin its work in the McGill College quarters at Fairview, destined to remain its home until 1925. The work of McGill in British Columbia paced U.B.C. to a flying start. In a letter to Dr. Young, written at the end of the first day of lectures, September 30, 1915, President Wesbrook wrote: “I think it is quite true that we have been more fortunate than any other Canadian University. I do not recall any which started with as many students or with as large a staff.” McGill College in fact supplied most of the staff and more than half the students for the first session. Subsequently, U.B.C. Chancellor the Honourable F. Carter-Cotton, who had also been Chancellor of McGill College during its nine years, wrote to Sir William Peterson, Principal of McGill:

For the purpose of this brief survey, the history of the University’s active life since 1915 may be divided into four periods: (1) 1915-1925, At Fairview; (2) 1925-1939, Into and Through the Depression; (3) 1939-1945, World War II; (4) 1945-1958, Expansion and the New Era. Before I came here in 1944, the University had two Presidents: Frank Fairchild Wesbrook, who died in office in October, 1918, and Leonard S. Klinck who succeeded Wesbrook in July, 1919. Up till 1958 Convocation has elected five Chancellors: the Hon. F. Carter-Cotton who retired in 1918; Dr. R. E. McKechnie, who died in office in 1944; the Hon. E. W. Hamber; the Hon. Chief Justice Sherwood Lett who succeeded Dr. Hamber in 1951, and Dr. A. E. Grauer, elected in 1957. The earliest years at Fairview were dominated by World War I, in which the University took its full part. The spirit of our first President as he faced his difficult war-time task of organizing a new institution is seen in the message which he wrote for publication in the students’ Annual (now known as the Totem) at the end of the 1915-16 Session:

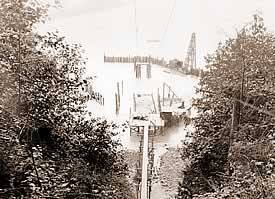

Inevitably the war dominated campus life. President Wesbrook himself commanded the contingent of the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps inherited from McGill College. A branch of the Canadian Red Cross Society worked feverishly at its self-imposed task of preparing and sending parcels to the students and faculty who were overseas. The student body was decimated by enlistments for active service in local and in other units. The University provided the personnel of “D” Company, with strength of 300, in the 196th Western Universities Battalion, and a reinforcing platoon of one officer and 50 other ranks. By the end of the war, enlistment totals had risen to 697 members of the University and of McGill B.C. Although a reasonably generous and broad-based curriculum was offered full-time students in the Faculty of Arts and Science, budget shortages in the war years seriously curtailed development of the Faculties of Applied Science and Agriculture. Of the total of 109 who graduated in the three war-time congregations all but one were students in the Faculties of Arts and Science. In 1917-18 it was found possible to enrol the first Freshman Class in Agriculture. The first regularly-enrolled class to graduate in Applied Science received their B.A. Sc. degrees at the Fifth Congregation in 1920. The most notable result of the University’s poverty in its first decade was the lack of suitable buildings and facilities both for work and play. The architects’ grandiose plans for the University buildings at Point Grey, approved in 1912, remained in the drawing board stage. These plans were part of the lure which had brought the first President to the Province from the Deanship of Medicine in the University of Minnesota, and from the day of his appointment until his death in October, 1918, Dr. Wesbrook laboured to effect the move to Point Grey. President Klinck took up the struggle in 1919 and in the following year succeeded in persuading the Government to adopt a policy of action; the 2,000,000 acres of University Endowment Lands were exchanged for 3,000 acres in Point Grey, and a bond issue of $3,000,000 was planned. Two further years of inaction followed until in 1922 the students, now 1,200 in number, embarked on their “Build the University” campaign which culminated in the presentation to the legislature of petitions bearing the names of 56,000 citizens supporting the campaign. This strong evidence of public interest in the University, added to an almost unanimous Provincial Press brought conviction to the Government, and they at once opened negotiations with the President and Board of Governors for the construction of the Point Grey Campus. Less than two years later, on September 22, 1925, lectures began in the new buildings, with a student enrolment of 1,453. Accommodation provided by the Government was limited to a strict interpretation of the “practical” needs of the University. All the buildings except the Library and Natural Science building were of temporary construction. There was no gymnasium; there were two inadequate playing fields, built by the students’ own labour; there were no dormitories; and there was no social centre other than the basement cafeteria in the Auditorium. But the prevailing sentiment of joy felt by the undergraduates who had experienced Fairview is shown in this editorial comment in the Ubyssey extra number published on September 23, 1925: “To those of us who began our academic careers in the catacombs at Fairview, the sudden accession to a wealth of light and beauty is positively bewildering. We are dazed with the appearance of architectural cleanliness and bewildered by our lineal freedom.” The Fairview years, however, had witnessed important developments in academic life and in other matters. In the post-war years, courses, both undergraduate and graduate, were developed in all three Faculties. The first Nursing and Health degree work to be offered in Canada was established in 1919. Honours courses made their appearance in 1920-21. A Summer Session was introduced in 1920, a Teacher Training course in 1923, and a Department of Education in 1924. Victoria College, closed in 1915, was re-opened as an affiliate of the University in 1920, offering two years work in the Faculty of Arts and Science. Until the Session of 1920-21 students paid no tuition fees, but that year a fee of $40.00 was imposed on all students. The work of the Extension Committee, which began in 1918, became, in 1920, a permanent feature of the University extra-mural service to the people of the Province. The year 1925 was the 10th Anniversary of the beginning of lectures at Fairview. Inaugural activities associated with the opening of the new buildings at Point Grey included the publication of pamphlets describing the University courses of study, buildings and laboratories, and enumerating publications of the Faculty. At a special Congregation, held on Friday, October 16, seven Honorary Degrees were conferred. Among the recipients were Dr. H. E. Young, “Father of the University”, Dr. J. D. MacLean, Minister of Finance and Education in the Provincial Cabinet, The Chancellor, Dr. R. E. McKechnie, and Sir Arthur Currie, Principal of McGill, who, appropriately enough, delivered the Congregation address. In 1928 and early 1929 the University seemed to be clear of its troubles. It was established at Point Grey; its facilities were sufficient for the student population of slightly more than 1,500 and were being improved; and, as times were good and governments and the public seemed at last to be more favourably disposed to the University, the prospect for steady expansion was bright. Discussions were held with Members of the Cabinet; plans were drawn by the University architects for two further wings to the Science Building, for the first unit of a permanent Arts Building, and for semi – permanent accommodation for Forestry and Home Economics. The Government grant for the academic year 1929-30 of $625,000 was, in relation to the students served by it, probably the most generous that has ever been made to the University. But the effects of these favourable circumstances did not last. Even before the depression came to undermine its economic prospects, the University’s security and independence were threatened by interference from a new Government. The details of the struggle over University policy on research and finance, especially in Agriculture, a struggle which eventually led to a Senate motion of non-confidence in the President, have been told in Tuum Est. The Commissioner appointed by the Government to enquire into the problems of the University, Judge Peter Lampman, concluded that all concerned had acted in good faith but that there were too many governing bodies in the University. The enquiry had barely cleared the air when the economic problems of the depression led to another attack on the University. In 1932 an “independent non-partisan voluntary committee” under the chairmanship of Mr. George Kidd, was asked “to investigate the finances of British Columbia with a view to recommending economies to the Government.” The Kidd Committee predicted that the Government would not be able to continue its grant to the University and implied that money might be better spent in sending students to other universities. By the time the Government rejected the committee’s recommendations, all members of the University – previously divided on financial policy – united to support it against this attack from outside. But unity did not solve the economic problems, and in 1932-33 salaries were cut from 5 to 23%. The President offered to cut his own salary by a further 13%, but this offer was declined by the Board. Even with salary cuts the vacancies in departmental staffs steadily increased; replacements were not made, and temporary staff members were not reappointed. A considerable number of dismissals had to be made of men whom the University could ill spare. A fortunate few went to other universities; a few hung on, on the periphery of the University, as under-paid and over-worked Assistants; some taught in the high schools and some left the academic profession altogether. For a few years all appointments on the University were for one year only, and tenure could not be guaranteed. The Summer Session was severely curtailled and most graduate courses were dropped. After 1933, however, the operating budget of the University was gradually increased, and its problems became not only financial but the much healthier ones that still face us; how to expand the buildings, courses and facilities so as to satisfy the increasing demands of an increasing student body. just as the overcrowding became intolerable, World War II broke out. When Canada declared war on September 10, 1939, the University, along with the other universities of Canada, found herself deeply immersed in the struggle. As it turned out, the impact of the war on the University was quite different from that of World War I, which was, in the main, an affair of fighting men. In this new, total war, not only was there need for men trained to fight on land, on sea and in the air, but the Allied Nations were confronted by an enemy equipped with every device of modern science. To meet the challenge of the Axis Powers, more and more urgent demands were made upon the resources of science and technology. In a struggle for mastery and survival the universities assumed a new and vitally important role. In his Annual Report for 1940-41, President Klinck described, in terms eloquent and memorable for their brevity, the resolute spirit of the University in meeting the unusual challenge:

At the outset neither staff nor students were quite sure what their role in the war effort ought to be. The University’s official policy evolved with the varying circumstances of the war, and as the Federal Government’s policy became clearer. The principal channels of communication between the University and Government with respect to academic as distinct from military war work, were the National Conference of Canadian Universities and the National Research Council. At the opening of the 1939 session, students were advised by the University – especially those in the sciences – to continue their studies, pending receipt of some authoritative direction. The N.C.C.U. and the National Research Council soon issued a statement advising all students in scientific subjects to remain at their university work until graduation. Thus was avoided, to a large extent, one of the most costly happenings of World War I, the premature sacrifice of highly-trained personnel in the Armed Services. In order to facilitate co-operative research, and a common approach to curricular and other problems, a War Services Advisory Board was set up by the universities of Canada to serve as a liaison between themselves and the Federal Government. Military training on the campus, regarded with indifference by the great majority of the student body in peace time, suddenly became popular. Registration in the C.O.T.C. Contingent more than doubled – from 98 in the previous session to 219 in 1939-40. For the first time graduates of accredited institutions were permitted to enlist in the contingent, as were also teachers who desired training to become cadet-instructors in the schools. Approval was given by Senate to allow students enrolled in the C.O.T.S. exemption from three regular course units in lieu of three units to be awarded for success in C.O.T.C. qualifying examinations. By intensifying the training schedule of lectures and parades, the Corps made it possible for its members to sit for their examinations during their first instead of their second year of training, as was formerly the rule. The innovation of granting academic credit for C.O.T.C. work was abandoned in the second year of the war, by which time military training had been made compulsory. Interest in the training provided by the Corps was increased as a result of instructions issued from National Defence Headquarters in June, 1940, requiring all units of the Canadian Active Service Force and the newly-formed Non-Permanent Active Militia Units to select at least half of their junior officers from among qualified C.O.T.C. cadets. Aided by this regulation, nearly all the cadets who passed the qualifying examinations in this first year of the war received appointments in one or other of the Armed Services. With the great demands made on university staff and facilities during the war came fresh recognition of their importance, and it is not accidental that it was during the war that the first money from the Federal Government came to the universities. The money was earmarked for specific purposes, it is true – War Service Bursaries, 1940; National Selective Service Bursaries, 1942; and various specified projects of research – but it was the beginning of those Federal grants to universities which have been so important to us since. In 1944, having served the University for a quarter of a century as President and for an earlier five years as Dean of Agriculture, President Klinck retired. He had guided the University through its infancy, through depression, and through war. Our facilities at Point Grey had been woefully inadequate in 1939. By the end of the war, faced with a sudden influx of veterans, they were so grossly inadequate that emergency action had to be taken. The emergency action, or rather the whole series of emergency actions – to find staff, institute new courses, open new faculties, perhaps most noticeably to find buildings for teaching and accommodation – made the postwar years the most exciting in our history. They were also the most exacting in the demands they made upon the abilities, energies and stamina of the teaching and administrative staff. The Federal Government’s open-handed assistance in the education of discharged military personnel, the generous policy of admissions adopted by the President and Board of Governors to reject no candidate who could qualify for entrance, brought an influx of veteran students which taxed to the limit the already overstrained resources of the University. The University was faced with many novel problems in this period. Nothing but the intelligent planning and grim determination of all concerned, working as a team, could have achieved solutions. Looking back now, I remember many moments when some people must have wondered whether or not we would survive the strains. But I also remember with pride the unfailing courage with which the University, within the short span of three years, accepted and provided degree work throughout a twelve-month session for three times as many undergraduates as it had been used to. The student population rose from 2,974 in 1944-45 to 9,374 in 1947-48. Courses of lectures, lecturers and facilities were found for them all. It should be remembered, too, that the entire cost of these undertakings was met out of an annual operating budget, and that no provision was made for building funds and no bond issues were made, as in business and industrial procedure, to deal with new and necessary financing. But every effort was made to meet the emergency. The Board of Governors gave me “general authorization to take such emergency action, in consultation with the Chancellor and others, as may be necessary in respect of staff, equipment and accommodation.” There was no time to wait for formal approval of the Board of Governors to secure lecture-room space when hundreds of students were enrolling for whom no such facilities were in existence on the campus. Plans for new buildings had been made during the last two years of the war but the most advanced of these were still in the blue-print stage when the tidal-wave of veterans arrived. In the session 1944-45, the registration was 2,974 (of whom 150 were ex-service personnel); in 1945-46, registration more than doubled with 2,254 veterans in a total student body of 6,632. A conflict of priorities at once arose between the urgent need for classrooms and for student housing. Surplus Army and Air Force camps supplied both needs. Fifteen complete camps were taken over by the University in the course of the 1945-46 session alone. Twelve of these camps were dismantled; their huts were brought to the campus on trucks and there erected and equipped as lecture rooms and laboratories; the remaining three were adapted for living quarters, one each in Acadia and Fort Camps, the third on Lulu Island. Still another camp, situated on Little Mountain, in Vancouver, was converted into suites for married students. Registration continued to mount. In the Summer Session of 1946, there were 2,398 students as compared with 861 in the previous summer. A special short Winter Session from January to April in 1946 had 1,098 registered students. In the regular Winter Session of 1946-47, the numbers rose to 8,741 and reached their highest point of 9,374 in the following year. Gradually from this summit registration subsided: in 1948-49, it was 8,810; in 1949-50, 7,572; in 1950-51, 6,432. In the process of settling back to what might be considered, from past experience, to be a normal student population, an unexpected feature made its appearance in the remarkable increase in non-veteran registrants. In 1946-47, the veterans numbered 4,796 and composed 53.4% of the entire student body. Even so, the remaining 46.6%, numbering 4,239, showed an increase of nearly 1,000 non-veteran students over the numbers of the previous year. In 1947-48, the total of non-veterans rose to 4,917 or 53% of the student body in the year of maximum registration. At this point, we felt safe in estimating that the normal enrolment of the next ten years, when the educational needs of ex-servicemen had been met, would be 5,000 to 6,000 students. In the next year, 1948-49, these predictions began to appear to have been too conservative; registration of non-veteran students numbered 5,580, or more than double the total registration (2,476) ten years earlier. The number has never since been below 5,000. Registration of veteran students dropped sharply at the rate of 1,000 a year from their maximum number of 4,796, in 1946-47, to 336 in 1951-52 in a total student body of 5,548. In the following year the low point of post-war registration was reached, numbering 5,355. From this date the number of undergraduates has increased each year, at a slow rate to begin with, more recently with almost alarming acceleration, until today, five years later, the registration for the session of 1957-58 has reached 8,986, less than 400 short of the highest post-war registration, in 1947-48. This increase in student registration is to be ascribed to the rise in the birth-rate and to the greatly increased immigration into the Province, to a high level of prosperity, and to the growing demand for university education. Moreover, the growing reputation of the University increasingly brings students from abroad. The years since the veterans left us have been a time of steady expansion. They are close in memory, however, and I do not intend to repeat the details of our development. They are easily available in my Reports and in Tuum Est. The campus changed radically between 1947 and 1951 with the erection of twenty new permanent buildings. Since 1955, when the Provincial Government announced a grant of $10,000,000 for buildings, and since we have begun to receive Federal Government grants on a large scale, it has begun an even more extensive change. As the funds from the Development Campaign become available, we shall be able to implement the new Development Plan. It is trite to say that buildings do not make a university, but we must remember that they are very necessary. As a list of buildings makes tedious reading, I have included in this Report many photographs showing the development of the campus. To appreciate the growth of the University, however, each building must be peopled by the imagination with the many students who have spent four or five years in it. Fortunately, my very brief history can have no tidy conclusion. Neat summaries of the history of an institution can be made only when it is static – or dead. The University of British Columbia is very much alive and I hope it will continue to develop as it has done in the past. |

|